James Fisher's oil on linen works look like multimedia collages, but they are created entirely with paint. The artist gave us a detailed account of his unique process and how he achieves the mesmerizing textures and effects in his paintings.

(You Won't Hear My Step and Beyond Ice and Night and Fear) were made by accruing imagery and layering it over and over. The surface was then abraded with Stanley Knife blades and sandpaper to reveal aspects of images that had been hidden.

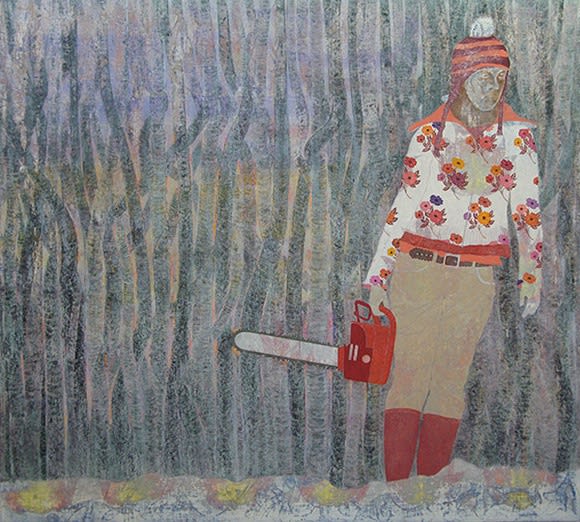

You Won't Hear My Step, 2008, Oil on linen, 54 3/8 x 59 7/8 inches (138 x 152 cm)

An early stage of You Won’t Hear My Step, unrecognisable from the finished image, included the initial placements of a crow motif. These were drawn in wax and charcoal, then "fixed" with the bronze-peach oil glaze that can be seen in areas of the image. Then a stage further on in the painting, the crow motif was condensed into an outline. A flame motif, appropriated from a hazard warning sign was arranged in a repeating pattern across the surface of the picture and is still visible in the final painting. The figure, trees and horizon line of the completed picture were then added. The flame motif introduced earlier is still visible "through" the figure and below the horizon line. Wax was added to the paint in the tree areas to assist in the knife scraping and polishing.

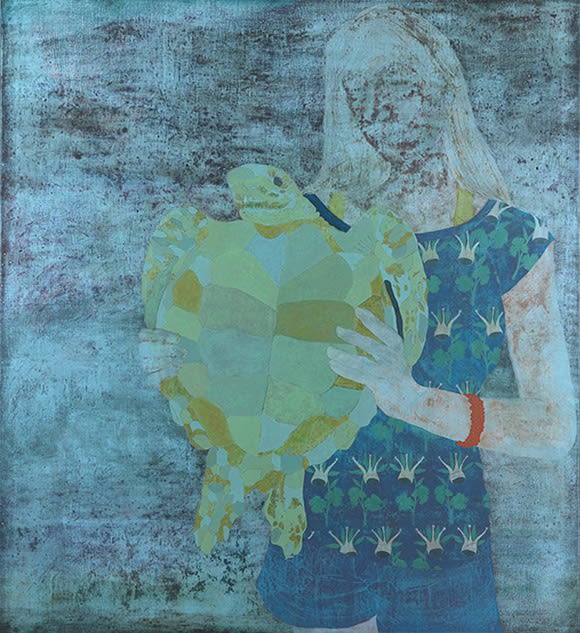

Beyond Ice and Night and Fear, 2008, Oil on linen, 54 3/8 x 59 7/8 inches (138 x 152 cm)

Beyond Ice and Night and Fear, equally, has a variety of paint handling on the picture surface. The salmon-pink sky is scored with a knife blade. The bough of the tree in the centre of this detail is scumbled with a Vandyke brown over a metallic undercoat. I make this metallic paint myself using bronzing powders and damar varnish. The flowers motifs, whilst crisply painted and designed to define the perimeters of the figure with clarity, are nevertheless delicate and translucent.

The Air of Highland Mary, 2008, Oil on linen, 68 1/8 x 62 inches (173 x 157.5 cm)

(The Air of Highland Mary) was intended to describe a kind of journey, and it was much more influenced by looking at watercolor landscapes by artists traveling on the Grand Tour, for example. To arrive at the image in The Air of Highland Mary is to describe the narrative of making the painting. In order to make this clear, it was important to make explicit the process of the paintings’ travel towards uncovering an image. Watercolor painting is, by the nature of its translucency, made in one take. A watercolor painting is built up in increments of tonality, beginning with the white of the paper support. Its translucent or glaze system of pigmentation uses the white of the paper for its whites and pale tints. These are then laid and overlaid with further glazes to produce the darker areas of the picture. To replicate this, an amber coloured ground was laid, over which the outline of the figure was sketched in. In the field of the painting, around the figure, the picture surface was then flecked with gold-coloured bronze powders. This stage was then painted out with a half-chalk ground.

Detail from The Air of Highland Mary

The sketch of the figure was still faintly visible beneath the half-chalk ground, and, as the surface of the picture was abraded to make it smooth, the bronze powders emerged to illuminate the ground....Gesso and half-chalk grounds provide a painting surface that is semi-absorbent and has characteristic properties of illuminating the pigment in subsequent substrates of paint film. A ground of this type has the principal drawback of a long drying time. Paint layers of different constitutions expand and contract at different rates as they dry, so careful consideration must be made with regard to the order of paint substrates of varying drying times to avoid the cracking and instability of subsequent layers. As the half-chalk ground in this instance would not be the bottom-most layer in the painting structure, a fast-drying alternative was required...The half-chalk ground was applied uniformly and in viscous consistency. When dry, a second coat was applied with particular attention paid to eradicating prominent brushstrokes apparent in the first: the brushstrokes in this layer were made in a direction opposite to the first. The half-chalk ground was then allowed to completely dry over a period of several days. When this was complete, the linen support was removed from its stretcher and tacked onto a firm, flat, flaw-free support, so that the picture surface could be abraded. This was done, using an increasingly fine grade of glasspaper, so that the resulting picture surface was porcelain-smooth, and traces of the figure outline could be discerned. The weave of the linen was filled and eradicated by this process, and the china-white surface of the painting was flecked and warmed by the gold of the underlying bronze powders. The linen support was then stretched back onto its wooden frame.

The resulting painting surface provided a very sympathetic support for the remainder of the painting’s process involving the application of pigment powder. The surface was semi-absorbent and smooth so that the pigment could be moved over it with a flexibility that offered a great deal of control. Pigment would adhere to the surface where it was required and could be removed precisely and effectively where it was not. The pigment powder was applied dry at the outset, using a cotton cloth. As more certainty regarding the image was reached, a fixing solution of damar varnish and linseed oil was introduced, using the same cotton rag, moulded into points or bunched into a kind of pouncing pad as required. In this way, the image was arrived at in a very fluid, exploratory manner. The traces of the initial outline through the hard-chalk ground offered guidance at the outset of discovering the figure of Mary and the turtle.

Cock-a-doodle-do, 2022, Oil on linen, 78 3/4 x 72 inches (200 x 183 cm)

(Cock-a-doodle-do and Hyacinths and Thistles) were made using a new process developed during COVID lockdown. I make drawings in gardens and arboretums to bring back to the studio. There is one nearby, full of strange and beautiful plant specimens: Blue Atlas Cedar, Indian Bean tree, Giant Redwood, Sweet Gum tree, Swamp Cypress and Mulberry. The drawings I make there are collaged together with fragments of other pictures, drawings from Indian miniatures, for example, and reorganised to plan new paintings. These collages also include drawings of the Studio Models that I make to inhabit the paintings, from discarded toy parts and fabrics from Japan.

Once these collages are assembled, I then use them to inform the paintings. The paintings are made on gold grounds, which flicker magically to highlight or obscure a half-seen figure or the mirage of a dreamlike glade. The palette I use is dialed-up and borrowed from Technicolor films like Victor Fleming's The Wizard of Oz or from video games such as Yoshiaki Koizumi's Super Mario Galaxy. The grounds are made using the same bronzing powders I used in earlier paintings, with damar varnish and linseed stand oil.

Hyacinths and Thistles, 2022, Oil on linen, 47 1/4 x 59 inches (120 x 150 cm)

Cock-a-doodle-do and Hyacinths and Thistles were then made in smallish sections. They are first painted in oil onto a sheet of plastic, using the collages as a guide. The plastic is then turned over and "stamped" or printed into the painting, adjacent to, or even on top of, a previous section. A Japanese baren is used to press the image onto the canvas, replicating Japanese woodblock techniques. When all of the sections of the painting are completed, and this layer of the painting is resolved, colored oil glazes, with a high pigment content, are used to reconcile the image, drawing the sections together and (heightening) the color in the painting. These are brushed on and then blotted with tissue to make a glass-